Quantitative Indicators of Personality Types: A 2D Matrix Approach

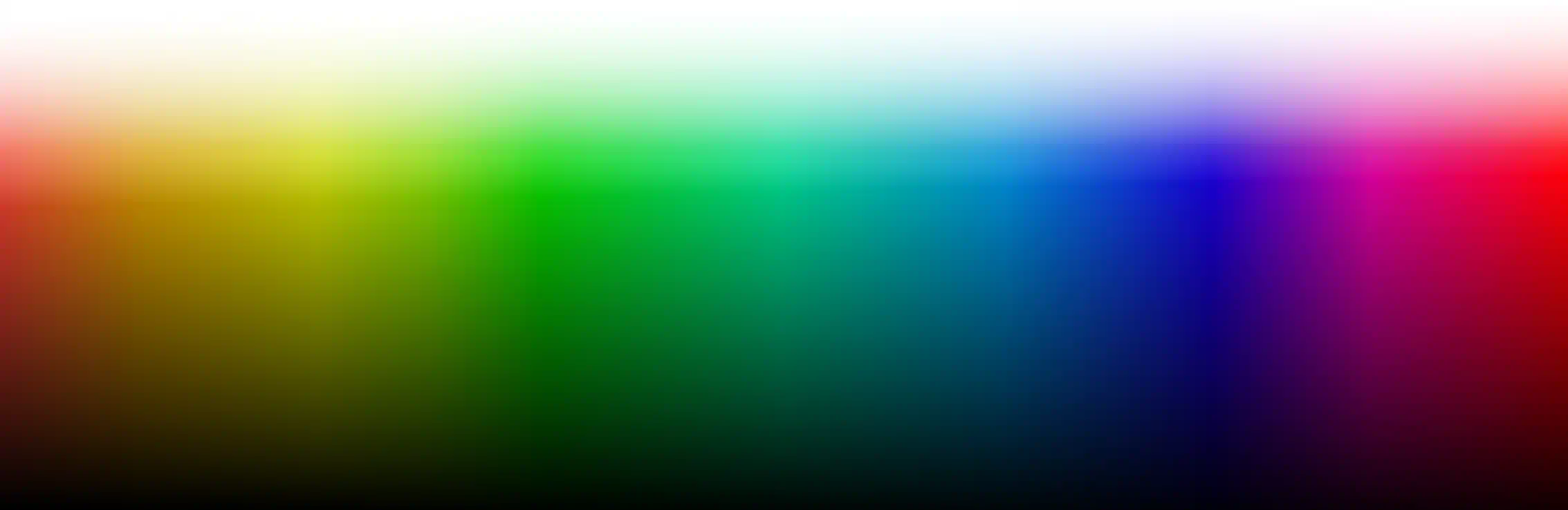

When we discuss personality types, the focus often lies on qualitative aspects—behavioral traits, preferences, and methods of interacting with the world. But what if we introduced quantitative indicators into this approach? This question arises within the context of any sociological framework and can be visualized as a 2D matrix. This matrix might resemble a color selection tool in graphic editors: the X-axis represents personality types, while the Y-axis is a social scale.

The Personality Types Matrix

Let’s refer to this concept as the "Personality Types Matrix."

X-Axis: Personality Types as a Color Gradient

Visually, the X-axis is a gradient from violet to red, covering the full spectrum visible to the human eye. The colors we see are not random; they are representations of specific frequencies within the visible light spectrum, ranging approximately from 400 to 700 nanometers. Violet, at the lower end of the spectrum, corresponds to higher frequencies, while red, at the upper end, aligns with lower frequencies. This frequency distribution is a direct analogy to personality types, where each type can be thought of as corresponding to a specific "frequency" or resonance within the human psychological spectrum.

Each point on the X-axis can be represented by a color code in the RGB (Red, Green, Blue) format, which captures the blend of primary colors to create a specific hue. Similarly, personality types can be seen as unique combinations of traits, forming a harmonious whole. For instance, if we use the 16 Socionics types, each type would occupy a distinct band on the axis, representing a particular "harmonic frequency" of human personality. This creates a continuous spectrum of variations for each type, much like the smooth transitions of color from one shade to another. In this way, personality types correlate with specific frequency harmonics, reflecting both the diversity and subtle nuances that exist within human behavior.

By mapping personality types to a visual spectrum, we can illustrate why different individuals with the same general type might still exhibit unique characteristics. Just as two shades of blue can be slightly different in hue, two individuals of the same personality type may show slight variations in traits. This analogy not only makes it easier to understand the fluidity of personality types but also highlights the interconnectedness between seemingly different individuals.

Y-Axis: The Social Scale

The Y-axis demonstrates a shift in color from black to white, representing a social scale. The lower end, closer to black, corresponds to maximum social dependence—where individuals are fully integrated into social norms and expectations. A clear example would be young children, whose dependence on society (parents, family) is at its peak from birth.

This scale does not correlate with traits like introversion or extroversion. In an ideal society, where decisions are made by well-developed representatives of Homo sapiens, the social scale might align with a chronological age scale. However, this is not the case in modern civilization.

The Role of Social Institutions in Personality Development

Social institutions, developed over millennia, often fail to encourage creativity. With the rise of AI, the day is near when machines will be able to predict life paths based on one's social context. This isn't because AI is inherently intelligent but because humans have built systems over thousands of years that restrict developmental potential.

Example: In certain Asian cultures, preschool-aged children are often treated as "little deities," allowed almost everything. Yet, upon reaching school age (5-6 years), societal attitudes shift drastically. This sudden change can be traumatic, embedding early childhood as a "golden time" that many unconsciously yearn to return to throughout their lives.

The Psychological Social Scale

The social scale is not about physical age but psychological maturity. At the beginning of the scale is a newborn, entirely dependent on the mother, family, community, and state. At the other end stands a wise individual, naturally inclined toward complete independence from society.

This psychological age encompasses not only maturity but also the ability to socially adapt and exhibit creative independence.

How Social Institutions Shape Personality

All cultures possess mechanisms that limit the individual's desire to explore and create. These mechanisms can be formal (schools, laws) or informal (traditions, societal expectations). Below are several examples:

- Education Systems: In many countries, educational institutions aim less to develop creative abilities and more to prepare individuals for existing economic roles. This system, established in the 19th century, remains largely unchanged in its primary goal—to ready individuals for participation in existing economic structures.

- Traditions and Customs: In conservative communities, traditions often dictate what behaviors and thoughts are deemed "appropriate." Straying from these norms can result in social isolation, making it challenging to express individuality.

- Corporate Structures: Many modern companies adhere to strict corporate norms, valuing adherence to standards and company goals over individual contribution. Creative personalities frequently feel out of place within such frameworks.

Quantitative Indicators in the Context of Personality

The Personality Types Matrix not only describes qualitative traits but also allows for a quantitative assessment of an individual’s social context. By positioning each personality type as a point on the gradient and social level as its vertical position, a comprehensive view of social interaction can be obtained.

Practical Applications

- Corporate Teams: In corporate settings, the matrix can be used for optimal team composition. For example, a team with a broad range of types on the X-axis but a high level of independence on the Y-axis may prove to be more innovative.

- Educational Programs: In education, this matrix can help develop personalized learning approaches, considering both personality types and each student's social context.

- AI Prediction: AI can analyze human development trajectories based on their position in the Personality Types Matrix. This can lead to tailored recommendations for both professional and personal growth.

Conclusion: The Future of Personality Analysis

We stand at the threshold of a new era where AI and big data are poised to revolutionize our understanding of personality and its development. Visualizing personality types and social context through the matrix makes this analysis more accessible and comprehensive. In the future, this may become the basis for more accurate and effective social and educational systems.

Each individual will be considered not only through the lens of their personality type but also in the context of their social position and growth potential. This will not only facilitate better self-understanding but also help individuals find their place in a complex and multifaceted world.